- Home

- Winkler, Philipp;

Hooligan Page 18

Hooligan Read online

Page 18

“Thanks, Heiko,” she said and tried to regain her composure.

I nodded and said, “Have fun at college.”

Then the taxi came. The driver got out and stowed the suitcase in the trunk of his cream-colored car. I was glad Hans stayed inside and didn’t come outside and make another scene. I raised my hand, said, see you soon, or something like that, but Manuela came over and hugged me. I don’t know why, but somehow I sank into the embrace of my older sister. She pressed herself against me, and I felt her cheek on my shoulder. Her warm breath against the 96 logo of my jersey with the name Dworschak and the number 22 on the back. My gaze connected with that of the taxi driver, who leaned against the driver-side door with arms crossed and waited for our farewell to end. I didn’t care if he saw me like that. Some stranger.

Then something slipped out of me: “I miss Mom too.”

Manuela pushed me away, looked at me aghast, as if I’d just held out a dead rat.

She said, “What? No. I didn’t mean that at all!”

Then the taxi driver looked away because it was none of his business. He climbed inside. Manuela opened the door, but then came back after all. I must have been standing there like a fucking idiot.

“Heiko, I’m sorry. I didn’t want to—”

She didn’t finish the sentence, looking past me. I turned around. The light in the hallway was on. And when I turned back toward her, she climbed into the taxi and waved. Then she drove off. Left me all alone. In the driveway. In this house with the cold, dark hallway. With the door to my room that I always locked, never left open. With Mie. And with our father.

———

Kai didn’t have to beg me very long to join in the celebration, and I agreed to go clubbing with him. Even though I’d hoped a little that he’d take it easy at first. After all, he’s still pretty worse for the wear, but of course that wasn’t even a question for Kai. Goes whole hog. I wasn’t allowed to help him with anything. For example, climbing stairs or getting up. Even though he pressed his lips together and held his breath in pain, he wouldn’t accept help at all. He walked like he was walking on eggshells, and as if his upper legs had been replaced by tree trunks. But who cares, if one evening going out and drinking eases all that, then I’m definitely for it.

“I can ask if they have a bag for you here,” I say. We sidle up to the bar and I order two beers. “We’ll just cut out two holes for your eyes and that’ll do.”

He laughs derisively and says, “True beauty cannot be tarnished, dude.”

He adjusts the bandage across the bridge of his nose. His battered face still has the color mixture of a fruit basket. The Band-Aids and the bandages don’t make it much better, even if they cover the bulk of his face. He looks like he’s escaped from a horror film, and I tell him he shouldn’t get his hopes up too much he’ll find something to screw right away, and that, first and foremost, today we’re raising our glasses to the beginning of his recovery and his speedy return to the field.

“Ulf sends his greetings,” he mentions in passing, and lifts his glass of beer to his mouth with a slight tremor.

The bass beats of a Eurodance mix boom across the dance floor, still sparsely occupied behind us.

I say, “Hmm,” while the first sip is still running down my throat. I put it down, lick the suds from my upper lip, and ask when he saw him.

“He called this afternoon. They’re in Cuxhaven for a couple days. Wanted to hear if my face was slowly growing together.”

Kai turns around, leaning against the bar with his elbows, and briefly closes his eyes in pain. I also lean back, and together we watch the dancing dots of light on the waxed dance floor.

“You still hurt all over?” I ask without looking at him.

“Mhmmm,” he hums in confirmation, “compressions, contusion. Busted rib. At some point I stopped listening.”

He squints, looking at his glass from above and clucks, “Whatever. How was the match?”

I tell him about the Frankfurt tour. That the two skins from Langenhagen went along but didn’t cause any trouble. That we may have had to concede a clear defeat, but nothing else was in the bag. And that I’m thinking of getting a pair of hiking boots with tread for rainy weather and wet footing, so I don’t slip all the time and fall on my face.

“And anyway, it wasn’t the same at all. Without you guys, it just doesn’t rock. Just make sure that you get back in line soon, you fart.”

He nods to himself, nipping at his beer, and, lost in thought, watches the DJ on the stage who’s turning knobs on his mixing console as though bored. I look at him, and suddenly have to laugh.

Irritated, he looks at me and asks, “What’s wrong?”

“You have your undershirt on wrong, boy.”

Kai pulls his chin into his throat, looking down at himself. He reaches into his open shirt and pulls the label of the undershirt from the collar.

“Oh, crap. I was asking myself the whole time why my throat was itching so much.”

He puts down his glass and say he’s going to pop over to the toilet to pull the thing around right.

I order us two more overpriced kiddie beers and look at my smartphone to see when the draw is for the next round of the German Cup. Then I check my emails. Tomek had sent me a temporary link to the pics from the Frankfurt match. I download it and scroll through. Terrible quality. Shaky. Raindrops on the lens. You couldn’t recognize next to nothing. I roll my eyes, drink the beer, and order myself one more. At some point, I look at the clock. Kai’s been in the bathroom for almost fifteen minutes. I can’t help thinking of Leipzig and how Jojo and I waited and Kai didn’t come back, and an uncomfortable feeling gathers inside me. Such bullshit. We’re here in Hannover. What could happen to him here? It’s completely ridiculous to think stuff like that now. My phone rings. Kai’s number.

“Dude, what’s up? Did you fall in?”

I immediately notice from his voice that something’s not right. It has such a disturbing tone: “Almost. But. Can you just come?“

I cross the dance floor and dodge a couple people jumping around who are clearly tripping and have their heads pointed toward the ceiling.

“Kai?” I call as I come into the bathroom.

The smell of piss is already pungent, even though it’s still pretty early in the evening.

“Here,” a voice responds, “second stall.”

I want to push it open, but the door is locked.

“What’s up?”

“Wait,” he says, and I hear how his hand rubs over the surface of the door. “Wait a sec. Shit.” Then the lock clicks open. “So, it’s open.”

He sits on the closed lid. Holds his iPhone with both hands and fidgets with his legs.

“Close the door, all right?”

I do it and ask, “What’s up? Should I call a nurse who helps you wipe your ass?”

“Knock that shit off for a sec,” he says and sucks the snot up his nose. Had he’d already done some blow?

Then he looks up at me. I can immediately see that something’s not right. His eyes are tear-stained. The pupils dart from left to right but don’t appear to look anywhere really, don’t respond to my gaze although I’m standing right in front of him.

“I …” He swallows, his shoes tapping a fast rhythm on the tiles. “I can’t see anything.”

“What, you can’t see anything?”

“Heiko! I. Can. Not. See.”

His voice is unsteady, as if he’d just cried.

“What happened?”

I crouch down in front of him. His gaze briefly stays up. Then he appears to notice that I’ve changed my position, and sinks his head slightly. I wave my palm in front of his eyes.

“Knock that shit off,” he says.

“So you do see something.”

“Yeah.” He exhales. Stutters. Searches for the right words. “No. A little. Changed my clothes, and then. First there was some kind of spark. From outside my field of vision. Thought at first I’d accide

ntally looked at the light too long. Went over to the sink and washed my eyes. Then I went over here because it didn’t get any better.” His throat produces gurgling sounds. “Then the curtain closed.”

“The curtain?”

Because his jittering was also driving me completely crazy, I placed my hands on his knee and he finally went still.

“Dude!” he exclaims, and the moisture of tears spills over his cheeks. He wipes it away. “Just black. Like a black curtain. I can see almost nothing anymore. You get it now?”

“Fuck. Okay. Wait. I’ll call an ambulance. Should I call an ambulance?”

I get up and open the door.

“Heiko?”

I turn around again. He looks to the ground, turning his smartphone in his hands and once more tapping with his feet.

“I’m fucking scared.”

We waited in front of the club for the ambulance. He insisted I check if anyone was hanging around in the foyer because he didn’t want anyone to see him that way. When the coast was clear, he walked arm in arm with me, and I led him to the door with small, retired-people steps. Then I placed him by the street on a box for road salt and went back inside to fetch our jackets.

After we’d explained as well as possible what was wrong and Kai lay down, the EMTs started dabbing at his eyes. Bandages were placed over them while we drove to the hospital. They had no idea what it could be, and said we should wait for what the doctors would say.

All of that took forever. I spent half the night waiting in front of various examination rooms. Every time a doctor went by, I jumped up expectantly, but most of them stared at me with a mix of boredom and exasperation and passed on. I planted myself back on my ass.

The double doors open. Kai is led out, a doctor and a nurse on either side. I explode out of the chair, go to them. Kai has two round white flaps of fabric over his eyes, attached with transparent adhesive strips. He looks like an enormous fly.

“Well? What’s he got?”

The doctor, a blond guy, at most a couple years older than us, takes Kai’s arm and says with a Dutch accent, “Are you a member of the family or a friend?”

“Bud,” I answer.

He considers briefly, but then he remembers the meaning of the word. “Ah, okay. It looks like a detached retina. Caused by a rhegmatogene amotio retinae.” I look at him with incomprehension. “Retinal tear. He’s not just had it since today.”

“Hell if I know?” I say and throw up my arms, “And what does that mean? Does he have to stay here?”

The doctor sighs and looks like he was forced to talk to a kid who’s slow on the uptake, and says: “Take a look at your friend. Of course he has to stay here. Additional tests tomorrow. But I can tell you this much: because it was protracted and apparently not diagnosed or not diagnosed thoroughly enough, there’s some danger of an irreparable loss of function for the areas affected. And in this case we’re talking about damage on both sides. How could this not be recognized? I’m going to take another look in his file and perhaps speak with the colleagues who are responsible. A serious talk.”

“And irreparable, that means …” I start, but for some reason my mouth just stays open instead of continuing talking.

“Heiko,” Kai says wearily, “that means that I might stay blind.”

His head hangs low, as if someone had shot a tranquilizing dart into his neck.

“Partially,” the Dutch doctor chimes in once again. “At least there’s the partial danger.”

They lead him past me. I stand there. Have to process it first. When they reach the elevator and it opens up with a ding, I follow them.

“Irresponsible,” the doctor mumbles when he hands Kai’s arm over to me and remains in the hallway, “irresponsible.”

———

“Heiko, you’re getting on my nerves! No. All right. For real. Go home. I’ll fend for myself. Thanks for everything you’ve taken care of and all, but hey, I really need some peace and quiet. You’re driving yourself crazy. And me too.”

That’s how Kai sent me home. His parents sat on the other side of the room on two chairs a nurse had brought in. They’d been pretty restrained toward me recently, then took it up a notch and didn’t look at me anymore. For them, I’m probably the embodiment of what happened to Kai. That’s the only way I can explain it. When we were still small, and my parents and I still lived in Hannover, they lived right next door. Just as my mother often watched over me and Kai, they frequently took me in. They were something like my replacement parents those first years. Before we moved to Wunstorf. And now they ignored me like a piece of shit. But somehow I can’t blame them. I should have never gone for Kai’s stupid idea. Then we wouldn’t have gone to Braunschweig. He wouldn’t be sinking in a paper hospital bed like the picture of misery. Half-blind. Ulf would still be one of ours. I mean really. I wouldn’t be out of favor with my uncle. All this fucked-up shit wouldn’t have ever happened if I’d just said no.

I throw the tennis ball I’d found outside in the backyard and washed in the sink against the wall in my room. It bounces off and flies back to me in a precise arc. I throw it again. It bounces off. I catch it. Throw.

Arnim bellows up the staircase, “What the hell is all that noise?! I’m trying to call someone here!”

The dogs start barking.

He yells, “Shut up, you curs!”

They keep on barking. This time I didn’t aim good enough. I don’t catch it and it ricochets right into the ashtray beside me on the mattress. Cigarette butts and ashes made soggy by the still-moist tennis ball scattered over the sheet.

“Oh, shit!”

Arnim comes rumbling into the room. He has his phone in one hand and covers it with the other.

“Heiko. What’s the ruckus about?! Trying to sort something out right now.” He looks at my dirty bed. “You spilled something.”

What, you don’t say! He disappears back into the hallway. I can hear that he’s speaking an odd mishmash out of German and English. Instead of scraping up the mess and putting it back in the ashtray, I pull the sheet off the mattress. Then I pull up on the four corners so that the ashes slip into the middle of the resulting bag and stuff the whole thing into the trash can.

I go downstairs. A stack of old papers that are usually on the table in the living room are spread out on the floor. In their place, there are three open envelopes and a fucking mound of cash. Hundred-euro bills of a poisonous green hue stacked, fanned out, and countless fifties are spread out on top. I can’t even guess how much cash is lying there. The kitchen door leading to the yard squeaks, and I hear Arnim come in from outside.

“Yes. Yes. Ja. I will da sein. Okay. All klar. Ja, good-bye. Later.”

I join Arnim in the kitchen. He glances at his watch, the leather strap digging into his thick arm. No wonder his hand is dark and swollen. He reaches for a greasy dishtowel covered with coffee stains and uses it to wipe his dome, as if he was polishing a bowling ball.

I swipe one of his coffin nails and take a seat next to him at the table.

“Hey, you showing your face again, my boy?” he says. His lungs produce an annoying whistle in his throat. He clears his throat. He sounds like an old moped.

“What’s up? Who were you chattering with?”

“Well, I was just about to talk to you about that.” He lays his knobby hands on the surface of the table, making the pack of cigarettes jump about an inch.

“Listen up. You have to help me. Those were the guuuys”—drawing out the ‘i’ sound—“who have the tiger for me. They drove all the way across Eurasia with the creature. Tomorrow morning, so somewhere between four and six, they’re behind the border with the Polacks.”

I flick the ash from my cigarette, look him in the eyes because now I’m completely serious, and say, “That pit and all wasn’t just a fucking pipe dream. You’re really getting a tiger, right?”

“You can bet your bony ass on that, my boy!” He makes such a satisfied face, as if he’d just rece

ived the gold medal in wrestling. “Finish that cig. Then it’s time to go.”

“Sure, have fun,” I say, getting up, and want to retrieve a can from the fridge.

His hand wraps around my wrist. Tightens. I automatically flex my muscles, but I don’t pull away.

“You’re coming along, my boy. Doing a little tour. Doesn’t work solo.” He pulls something from beneath the table and says, “I let you live here, and I also want something in return.”

He’s lost it!

I say, “I already take care of the critters when you’re traveling in Eastern Europe. That’s compensation enough!”

He pulls his hand out more. Now I can recognize the black, ribbed transition from the grip to the barrel of a pistol. All these fucking years there was a gun under the table and I didn’t catch that.

“You’re coming along. No discussion. I like you, my boy, but don’t ruin that for me. My dream. I won’t let that slip through my fingers just because you don’t want to play ball.”

I can see he’s actually serious. That he’d actually put that gun to my head and force me to get into his fucking car. I’ve always considered him fairly crazy. Even back when we met. He used to hang out in Midas, alone, and everyone kept out of his way. Then he sometimes came over to me and just started talking, probably because he needed someone to chat with. And I also thought his stories were interesting. Maybe completely wacky, but funny in a sick way. But now I recognize he’s just a fucking lunatic. I could try to pull myself away now. Run up to my room, pack my stuff, and run off. If I’d even get that far. I feel dizzy. The kitchen starts to spin around me.

I say, “All right already. We’ll drive there and pick up your fucking tiger.”

He lets go of me. Says, “That’s my boy. Good man.”

I take out a beer and hand him one too. Then I take a seat.

“Don’t expect I’ll keep living here after that stunt,” I say, with complete sobriety, opening the can and knocking back a long, deep sip.

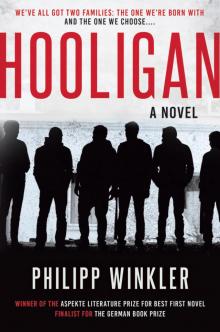

Hooligan

Hooligan